Some parents in America may work the 9-5 shift and are only

able to see their children a few hours out of the day. While their time

together is limited, it's a sacrifice that cannot be avoided and is one that

many can understand and relate to.

Some parents in America may work the 9-5 shift and are only

able to see their children a few hours out of the day. While their time

together is limited, it's a sacrifice that cannot be avoided and is one that

many can understand and relate to.

Imagine the exact scenario. But this time, with the mother,

father, or both parents working that same 9-5 shift on an entirely different

continent.

Immigration.

It was at the root of the very first American dream when the Pilgrims

migrated to the U.S in the 1620s for religious freedom. Those who have lived to

know oppression in their native lands and long for freedom and those who wish

to give their children the many opportunities that they weren't afforded know

its risks. They also know its rewards.

The number of families that migrate to the U.S has exceeded 13 million over the past 10 years, according to the U.S Census Bureau.

The United States. The world's super power. It is the "land

of opportunity" and is placed high on a pedestal. And sometimes, in making that

attempt to achieve the preferred future, families will undergo separation for

months and - many times - years.

It is, to be frank, not the best arrangement. However, many

confessed that migrating to the U.S. without their entire family was easier. They

could settle down first; then reunite afterward.

Pastor Charles Ozuruonye, a Nigerian native, migrated to

America with his wife in 1998. In their home country, they left their 2 sons,

who at the time of separation were 8 and 10 respectively. They are now 22 and

24.

Pastor Charles Ozuruonye, a Nigerian native, migrated to

America with his wife in 1998. In their home country, they left their 2 sons,

who at the time of separation were 8 and 10 respectively. They are now 22 and

24.

"I wish they could've been here by now... If we knew what we

know now, we would've done it differently," said Ozuruonye. "We filed for them

after we got here. If I knew that it would've taken so long, I would've brought

them too."

Ozuruonye and his wife currently live in New York along with three of their five children. Two of his children are American-born.

Unlike most families who migrate to America, Ozuruonye is

able to travel back to Nigeria to see his sons. He makes every effort to visit

annually. In fact, his last visit home was February of this year.

Dr. Peter Kleponis of Comprehensive

Counseling Services and The Institute for Marital Healing in West

Conshohocken, Pennsylvania says keeping in contact is crucial during the time of

separation between a parent and a child.

Sometimes the child may feel that they are to blame for their

parents moving away, but it all depends on their age.

"It's so important to have communication with the children. Letters, emails, whatever," said Kleponis.

He also suggests that parents "continue communication so that

the children know they have not forgotten them and continue reassuring them

that the parents are doing this for a better life."

The reason for separation should be made clear between the

parent and the child. However, sometimes those lines of communication aren't

always there, especially if the child is an infant during the split.

Yolanda Bailey, 18, grew up in Guyana, South America and

recalls the confusion she felt when her parents were not present.

Her parents migrated to America when she was just a few months old. As a toddler, she longed for her parents and didn't comprehend why she could not see them when she wanted to.

She and her older brother, Errol Jr., lived with several

aunts during that time.

She and her older brother, Errol Jr., lived with several

aunts during that time.

During the separation, Bailey's parents and a younger

sister visited once, sometime between the age of 5

and 7, Bailey recalls.

"I would cry for a long time because I always wanted to be with them," she said. "When we finally came to America, I was happy."

Although Bailey lacked the physical presence of her parents, they called often. In the meantime, she and her brother were surrounded by her aunts and cousins to give them the familial support they needed.

The time the parent spends apart from their child has a great impact on their state of mind. Sometimes it can result in resentment. Sometimes the child may feel that their once absent parents should not have authority over them. Or, sometimes, in the case of Bailey, the child may adapt with no rebellion during reunification.

But, does this child not have a right to feel abandoned?

"I consider it an emotional response, not a right," said Dr. Melrose Rattray, a professor at Medger Evers College in Brooklyn, New York. "You feel the distance and the lack of connection. What is required is an understanding of the time lost."

A Jamaican native, Rattray began her research on the subject

of immigration in the late '80s, early '90s. Her focus was on the psychological

effects of the children involved and the implications of parents leaving.

She and Dr. Claudette Crawford Brown, a University of the

West Indies academic, worked to develop the concept of "barrel children" -

children who have been left behind by parents who seek opportunities in foreign

nations. The children receive material possessions like sneakers, canned foods

and electronics from their parents via shipping barrels in lieu of direct care.

Crawford-Brown, in her seminal publication Who will save our children: The plight of the Jamaican child in the nineties published in 1999, explains that these children have surrogate parents like aunts, grandmothers and older siblings who are often unable to give them the emotional support that they need. These children don't, after all, belong to them.

The children may grow to carry a resentment for the parent who left them in the hands of sub-par caretakers, even though it proves to be in child's best interest in the long run.

"Our children won't remember where we were, they only remember where we were not," said Rattray.

In her soon to be published work on this phenomenon, Rattray addresses the recurring themes of disconnection and communication post-reunification.

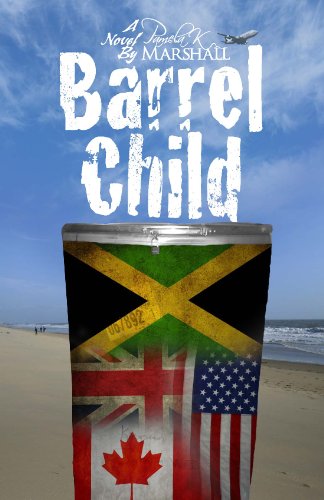

Jamaican author Pamela K. Marshall decided to create a work of

fiction from this very plight, entitled Barrel

Child. The book was released this year and follows the story of a girl's struggle to find

her place in today's world as a barrel child; she then fights to become a good

mother to her own children.

Jamaican author Pamela K. Marshall decided to create a work of

fiction from this very plight, entitled Barrel

Child. The book was released this year and follows the story of a girl's struggle to find

her place in today's world as a barrel child; she then fights to become a good

mother to her own children.

So, is it best for parents to emigrate at a time when their children are more ready to handle the matter?

"The younger the child, the more resentful," said Kleponis. "A teenager can understand that the parents have to leave for a better life for them. [But] the early years of life is for bonding. This is where the child feels they are loved... It's crucial. When they are separated, they lose that sense of security."

Reunification can go in any direction. Often times, it is a

joyous occasion. One of the biggest concerns, though, is how well the families

are able to adapt to each other during post-reunification.

"We act like we knew each other forever," said Bailey, since living with her entire family for 10 years now. "We always bonded and my parents were happy 'cause we're all together."

Bailey claims that her parents didn't expect her and her older brother to be in Guyana without them for so long. It was supposed to take three years, but it took eight.

"Imagine spending a couple months with your baby and then you have to let them go and the next time you see them they are walking and talking. It made them really sad," said Bailey.

The U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services process cases in the order

in which they are received. Petitions for a spouse, parent or minor of a U.S citizen are normally processed within 6 months

of the date received.

Although there is a set time frame for the various forms of immigration cases, the gargantuan case load being tended to by Immigration Services hinders the initial length of the process and so it takes longer than intended.

After filing for a relative, applicants may have to wait several years

"in line" because

of cases that were filed before them.

Once they reach the "front of the line," the U.S Department of State

contacts the relative and advises him or her to apply for an

immigration visa.

In most cases, when a relative has reached the

"front of the line," their spouse and child under the

age of 21 can also join them.

Bailey is currently a legal permanent resident in the U.S.

and lives in Ohio with her parents and other siblings. But the journey toward

reunification was met by some struggles to adapt to a new environment.

A culture shock is normal once a child migrates from familiar

surroundings to unfamiliar ones. It may be

difficult for them to make friends, adjust to the school system and the climate

change among other elements.

"I had never seen snow, so when we landed I was like what is this white stuff falling from the sky?" said Bailey. "I saw my dad with jackets for us and I thought, it's hot why do we need that? But then I started to feel cold...I used to say 'look I'm smoking!' I didn't really understand it, I thought it was cool."

Shock may spring all sorts of reactions from the child because they may have been accustomed to the lifestyles of their native home. Not only that, they may have a hard time adjusting enough to call their estranged parents, "Mommy" or "Daddy."

"If my grandma had been taking care of me, that's my mother. Or my aunt is my mother. I think so because I don't know you. So when I join my own mother, fifteen years later and she is expecting me to call her mama it becomes awkward...Not just the name, but the function and the feeling that comes with that," said Rattray.

Parents play a large role in assisting their children in transitioning to American customs. The act of patience goes a long way as well as a

firm foundation.

"Churches

help people preserve the culture of their home land," said Kleponis."When you

go back to the early twentieth century in the Catholic church...there was a

different culture for each Catholic church on

Even if they are not affiliated with any church, Kleponis said, there are neighborhoods in countries like the U.S. that are populated with people of different cultures.

China Town in New York City is a popular example of this, along with the various neighborhoods that are well known for high populations of families from the Caribbean, Latin America and Europe.

By keeping close to such affiliations, the elements of a

child's native home may become less blurred with the passing of time. Simple

components such as foods and celebrations can trigger the reality that they are

in a safe place that is now their home.

"Time, attention and concern are the three main things that parents should consider during reunification," said Rattray. "Many things may have transpired while the parents were gone, the child may have been abused emotionally or physically, or they may have had a great life with the family they were with."

Above all, the new bond between the parents and child will gradually help in the child's emotional and psychological development.

Ozuruonye keeps his spirits lifted by reading a verse of scripture from Mark 10:27: "with God all things are possible." He meditates on this verse daily, keeping hope that his family will soon be together again.